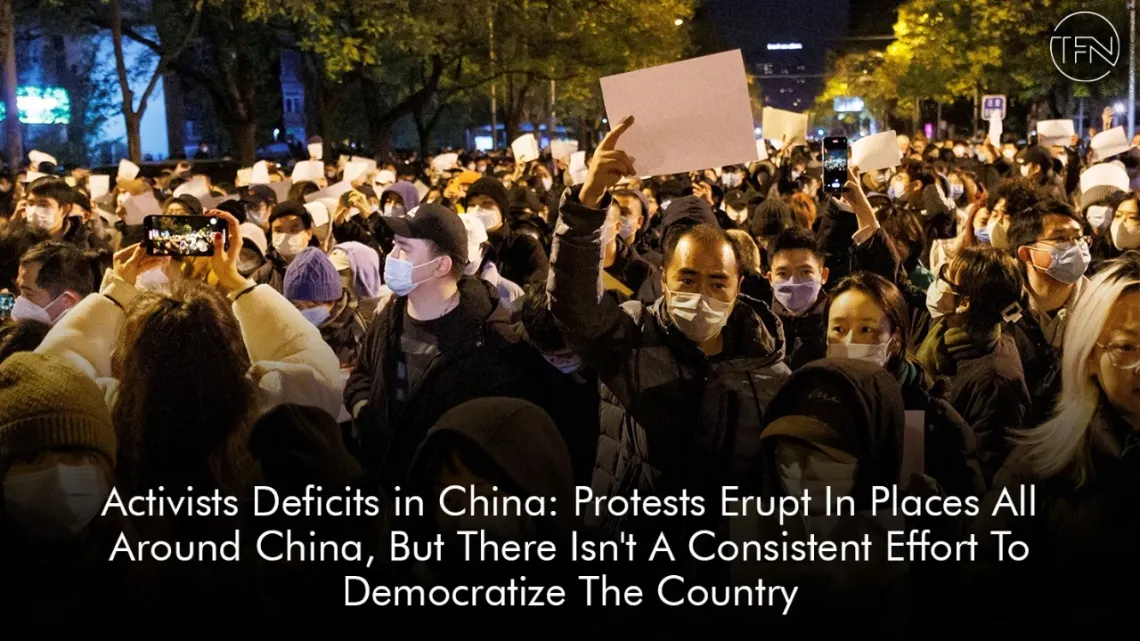

In a rare display of political discontent, protesters have taken to the streets of China's cities. While the majority of the protests have been directed at the government's zero-COVID policy, they have raised the possibility that a pro-democracy movement or perhaps a political shift akin to Taiwan may follow.

But this is doubtful, not least because China has too few young people to participate in the conflict as a result of decades of rigorous family planning laws.

A nation is said to be experiencing a "youth boom" when the percentage of persons between the ages of 15 and 29 reaches 28%.

People in this age group are more prone to question conventions, take part in protests, and advocate for change since they are the most economically active, politically engaged, and physically active members of society. Therefore, a nation may find itself on the road to political transformation, including perhaps democratization, when it is experiencing a youth boom.

In Taiwan and South Korea, that was the situation. Economic growth and pro-democratic enthusiasm both climbed as the proportion of young people rose, from 25% in each country in 1966 to a peak of 31% in the early 1980s. In 1987, when the median age of their populations was 26 years old, both nations' economies became democracies.

When the Arab world's median age was under 20 in 2010, the Arab Spring uprisings were also fueled by a youth boom.

China once appeared to be experiencing a similar trend. In China, where the median age was 22, the proportion of young people increased from 24% in 1966 to 28% in 1979. Growing political passion, albeit one that was not democratic, contributed to the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976. Political participation among young people also aided Deng Xiaoping's 1978 reform and opening up, which caused significant social upheaval.

The government responded to that turmoil by launching a three-year "strike hard against crime" campaign in 1983–86. But this didn't moderate the Chinese people’s rising pro-democratic ardor.

Tens of thousands of Chinese people hoisted a new emblem, the Goddess of Democracy, which was fashioned after the Statue of Liberty, in Tiananmen Square in Beijing in April 1989, when the proportion of youth was at its highest (31%), and they demanded speech freedom and an end to censorship. The movement was finally put down in June after a brutal crackdown.

The turmoil began in the province of Xinjiang afterward. Although there was not a youth surge in the area in 1989, the percentage of Uyghur youth exceeded 28% in 1996 and reached a peak of 32% in 2008.

The Ürümqi Riots, which erupted in Xinjiang the following year, began as a nonviolent student-led demonstration over the murder of two Uyghur factory workers but swiftly turned violent. There is a link between the youth boom and the Tibetan riots in Lhasa in 2008.

Young people are once again leading protests in China today. However, they are no longer as prevalent. When the median age in China was 42, the proportion of youngsters aged 15 to 29 was only 17%. And the percentage will only get smaller, possibly falling to 13% in 2040 when the median age is predicted to be 52.

Political change is challenging to achieve in a nation where the median age is over 40 and the young population is under 20%. The protest movement that arose in Hong Kong in 2019 to protect the city's democracy failed, in part, because the territory had reached political "menopause" with a median age of over 44. Ages 15 to 29 make up just 16% of the population.

Of course, repression also plays a significant part in putting an end to such movements, and China's leaders have not shied away from repressing, censoring, and subduing their citizens. However, the dwindling number of young people is ultimately robbing society of the resolve to fight for democracy.

Because there won't be enough youth to support benevolent reforms like the one in 1978, social rigidity is the threat that the Chinese authorities should be most concerned about.

The majority of the one-child generation are "little pinks," who prefer to defend the status quo over working for social change. Not just because older generations tend to favor the status quo, but also because their parents are not exactly equipped to lead a revolution.

They understand they will need to rely on the government for social security, health care, and the rest of their retirement safety net because they will only have one child to support them in retirement.

Because of the one-child policy, China's average household size has decreased from 4.4 persons in 1982 to 3.4 in 2000 and 2.6 in 2020, which has reduced families' needs and given the government more control. The disposable income of Chinese households fell from 62% of the GDP in 1983 to 44% in 2021. The average worldwide is 63%. Despite having experienced four decades of tremendous economic growth, China's middle class is too small.

A fractured, economically precarious populace may stage protests, but none that would be long-lasting or significant enough to overthrow a strong ruler, much less lead to a democratic transition. China may never escape the middle-income trap or undergo a political change since aging causes economic slowdowns.

Undoubtedly, China may need to pursue paradigm-shifting economic, political, and social changes as well as alter its foreign and defense policies if household discretionary income increases to 60–70% of GDP. A more Western-style political structure would result from this, and connections with the US would be strengthened.

However, despite these flaws, China's political system is not in immediate danger, even if continuing with this type of government will eventually lead to demographic and economic collapse. After its population started to decline in the seventh century, Tibet's political system continued to function for more than a thousand years.

Although it is far from certain, Chinese authorities should feel politically safe enough to switch back to a more benevolent Confucian system, with the government attempting to reestablish population sustainability and socioeconomic vibrancy.

Many people believed that China's economic opening would surely result in greater democratization when the country joined the World Trade Organization two decades ago.

Instead, China expanded its repression and censorship while producing anything and everything its citizens or the rest of the world could desire. A sufficient number of Chinese people are needed for China to guarantee its future and continue its path toward democratic reform.